A. H. Davenport: Furniture from the Gilded Age to the Modern Age, 1880–1950

Nancy Carlisle, Historic New England

Chest of drawers with shelves, A.H. Davenport Company, ca. 1890. Private collection

Serving table, A.H. Davenport Company, ca. 1890. Private collection

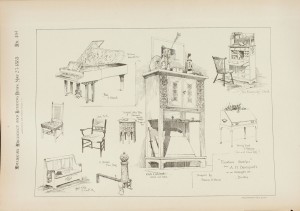

Francis Bacon furniture designs, American Architect and Building News, May 25, 1885

The A.H. Davenport Company, founded in 1880, was one of the nation’s premiere producers of expensive, Gilded Age furniture for a clientele with unprecedented wealth and profound desires to display their wealth. The Davenport Company furnished ornate mansions, elite clubs, marble-floored banks and some of the country’s most beautiful libraries in partnership with architects such as H. H. Richardson; McKim, Meade & White; and Peabody & Stearns. Davenport’s commissions included the Iolani Palace in Honolulu, Chicago’s Glessner House, the Vanderbilts’ Breakers in Newport and McKim, Mead & White’s 1902 restoration of the White House.

Albert Davenport was a brilliant and charismatic businessman in an age of entrepreneurs. One colleague distinguished Mr. Davenport for his “energy and forceful character.” The A.H. Davenport Company established a new model for manufacturing furniture precisely because the company was run by a businessman — rather than a craftsman — who worked in partnership with a talented designer. Albert Davenport possessed the acumen to hire Francis Bacon, an M.I.T.-trained architect, as the company’s chief designer in 1885. Bacon’s characteristic attention to detail emphasized the furniture as well as its artistic settings.

Eight years after Albert Davenport’s death, in 1914, the company merged with Irving & Casson to form the Irving & Casson–A. H. Davenport Company. The new company maintained showrooms in Boston and New York, and continued the tradition of working with private clients and architects to make high-quality furniture for homes, businesses, banks, churches and hotels.

The market for high-end furniture began to shrink in the 1930s with the Great Depression and increasing competition. High-end furniture lost market share to cheaper goods from the Midwest and the South, and — at the other end of the market spectrum — to a growing demand for expensive antiques. Irving & Casson–A. H. Davenport finally closed its doors and went out of business in 1974.

Nancy Carlisle graduated from Bates College with a bachelor’s degree in cultural studies. After graduation, she acted as curator of the college’s art collection. Ms Carlisle earned a master’s degree from the Winterthur program in early American culture. She then became a curatorial assistant for the Essex Institute (now part of the Peabody Essex Museum) in Salem, MA. Ms Carlisle is a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s program in American civilization. She was a curator for the Atwater Kent Museum in Philadelphia after finishing her course work. She has been the senior curator of collections for Historic New England (formerly the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities) since 1987.

Nancy Carlisle has contributed “John Ellis and A. H. Davenport: Furniture Manufacturing in East Cambridge, Mass., 1850–1900” to New Perspectives on Boston Furniture (forthcoming). She also wrote America’s Kitchens (2008) — with Melinda Nasardinov, and Cherished Possessions: A New England Legacy (2003). Ms Carlisle contributed “Eppes Ellery: Discoveries in the field” (2006) to Antiques & Fine Art *(Summer 2006) and “Revolutionary Acts; Selections from the SPNEA collection” to *The Magazine Antiques (August 2003).