Glitz Sparkle and Shine: The Wonderment of Dutch New York Interiors

Erik K. Gronning, Sotheby's

Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt, the “Castello Plan,” ca. 1670 (after 1660 original), ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Candlestand, New York, ca. 1725, gumwood

Portrait of Helena Jansen Sleight, oil on canvas, attributed to Nicholas Vanderlyn, ca. 1745. Courtesy of the Senate House, Kingston, NY

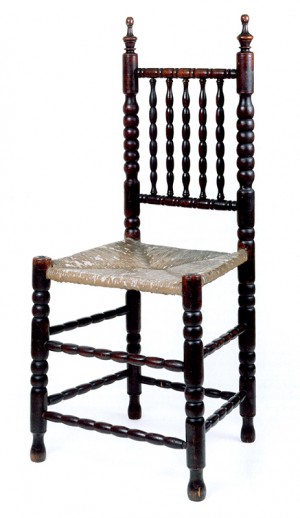

Spindle-back side chair, New York, ca. 1690, cherrywood

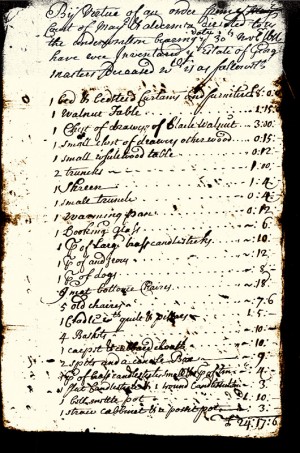

Estate inventory of George Masters

Erik Gronning will focus on the art and architecture of New Netherland. New Netherland, started as a business venture by the Dutch West India Company, was a culturally diverse society from its beginnings. In 1643, a French Jesuit from Canada, Isaac Jogues, visiting New Amsterdam was told that “[o]n the island of Manhate, and its environs, there may well be four or five hundred men of different sects and nations … there were men of eighteen different languages ….” The colonists who quickly settled along the shores of the Hudson, Connecticut and Delaware rivers were there to amass wealth, unlike colonists to New England--some of whom had emigrated from the Netherlands--who came to establish religious communities. The combination of materialism and heterogeneity gave the Dutch commercial colony a unique identity which New York retains to this day. Although New Netherland ceased to exist politically after 1664, when the British seized the Dutch colony and renamed it after James, Duke of York, substantial Dutch cultural influence flourished in New York, northern New Jersey and sections of western coastal Connecticut until well into the first half of the 18th century. Rural areas of New York retained their Dutch character until the early 19th century.

Seventeenth-century Dutch homes are readily identifiable by their steeply pitched roofs; pitched, sweeping and/or parapet gables; pantile roofs; and split, “Dutch” doors. Erik Gronning will compare the circa 1720 Lukas Van Alen House in Kinderhook, New York and the 1738 Leendert Bronck House in Coxsackie, New York with the 1668 House of the Seven Gables (Turner-Ingersoll Mansion) in Salem, Massachusetts and the 1677 Whipple House in Ipswich, Massachusetts, both of the New England homes built with distinctive multiple gables and framed overhangs.

The interiors of early Dutch homes were distinguishable by jambless fireplaces, bed cupboards, draw-bar tables, spindle-back chairs and kasten. Erik Gronning will focus on Dutch homes richly furnished through patronage of Dutch, Flemish and German merchants. International trade, including exports and stylistic influences from Dutch colonies, such as Batavia (Jakarta), Formosa (Taiwan) and Brazil, added to the cosmopolitan nature of New York interiors. Archaeological excavations have unearthed architectural remains, as well as remnants of the exotic, precious ceramics and elaborate glass which were used--and subsequently discarded--in early Dutch homes.

Probate inventories expand our knowledge of New Netherland’s material culture, and the inventories frequently place the objects’ use in a room-by-room context. The Duke’s Law of 1665 required an inventory of all decedents’ personal goods and real estate. May’s speaker will use the 53-page inventory of Jacob Jansen de Lange, executed on May 26, 1685, to bring to life the breadth and complexity of early Dutch New York interiors. De Lange’s inventory, exemplifying “glitz, sparkle and shine,” included 61 paintings and prints of many subjects, an East Indian cupboard filled with porcelain and earthenware (part of a collection of 350 pieces of porcelain), a gold-framed looking glass, a French walnut wood cloth case, a hat press and a small ivory trunk tipped with silver. Dutch New Yorkers, such as Jacob de Lange, accumulated and displayed exotic, worldly goods at a time when the small, but seafaring and entrepreneurial, Netherlands, recently freed from Spanish rule, had established its own, far-flung colonies.

Dutch New York homes generally displayed far more paintings than their New England counterparts. Anne Grant, who wrote about her stay in New York from 1756 to 1763, noted that a “best bedroom was hung with family portraits, some of which were admirably executed; and in the eating room, which, bye the bye, was rarely used for that purpose, were some fine scripture paintings; that which made the greatest impression on my imagination, and seemed to be universally admired, was one of Esau coming to demand the anticipated blessing ….” Dr. Alexander Hamilton observed, in 1744, that the Dutch “affect pictures much, particularly history, with which they adorn their rooms. They set out their cabinets and buffets much with china.”

Erik Gronning’s emphasis on ‘glitz, sparkle and shine’ also derives from the reputation of Dutch New York householders’ for scrupulous cleanliness. Dr. Alexander Hamilton considered it noteworthy that “[t]heir kitchens are likewise very clean, and there they hang earthen or delft plates, and dishes all around the walls, in the manner of pictures, having a hole drilled thro’ the edge of the plate or dish, and a loop of ribbon put into it to hang it by ….”

May’s speaker graduated from the University of Vermont with a bachelor’s degree in zoology and chemistry. He graduated from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, in 1994, with a master’s degree in entomology. He worked for the New York State Department of Health studying the effects of cockroach allergen on underprivileged children in New York City. He subsequently graduated from Sotheby’s course in American arts in 1997. Since then, Mr. Gronning has been a dealer in antique American furniture, and worked for the New-York Historical Society and the American Folk Art Museum. He returned to Sotheby’s in 2004, and currently serves as the head of the department for American Furniture and Decorative Arts.

Erik Gronning’s contributions to American Furniture (Chipstone) are: “Early New York Turned Chairs: A Stoelendraaier’s Conceit” (2001); “Early Rhode Island Turning” (2005) with Dennis Carr; “The Gaines Attributions and Baroque Seating in Northeastern New England” (2010) with Robert Trent and Alan Anderson; and “The Early Work of John Townsend in the Christopher Townsend Tradition” (2013) with Amy Coes. Contributions to Antiques & Fine Art include “The History of an Heirloom” (2002). The Magazine Antiques published his “Rhode Island Gateleg Tables” (May 2004). Erik Gronning and Dennis Carr (the Forum’s speaker in November) contributed “Early Rhode Island Turning” to The Magazine Antiques (2005). He wrote “Dutch Joinery in 17th-century Windsor, Connecticut” with Joshua Lane and Robert Trent for the Maine Antique Digest (August 2007).

Mr. Gronning also serves as a board member for the Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Among the institutions he advises is the Historic Warner House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.